There are multiple sayings, myths, and tropes that are associated with PA school so I wanted to unpack them a bit. All of what I’m about to share should be taken with a grain of salt. These observations are from my experience through didactic year of PA school as a 35 year old second-career student. Some of these tips might appear against the grain but that’s intentional. This is a list to make you rethink what it means to be a student. Your mileage may vary.

So without further adieu, and in no particular order:

You should go over what you learned in class when you get home.

So there’s this idea of being in class all day and then getting home and reviewing / studying everything you learned to help make it stick. On the worst days, you’re in class from 8-5. So what, you’re supposed to go home after and review an entire day’s worth of content? What does it even mean to “review?” Read it? Quiz yourself? Flashcards? You likely had 4-5 classes of differing, sometimes related, content. You’re supposed to go over all of it, regardless of when the next exam is?

Here’s my take. Likely you always have an exam coming up in the next couple of days, often multiple. So in my opinion your time is better spent on that content. Focus on short-term testable material that’s going to keep your GPA afloat. Besides, unless you’re planning to then review that same information from the day again at spaced intervals, it might not be worth your time to review content from earlier in the day because you’re probably going to forget most of it if the exam is more than seven days away. I think this is really critical to understand; there’s an illusion to feeling “caught up.”

Remember that you’re constantly battling the forgetting curve and when you start to fight that uphill battle matters. It might feel like you’re staying ahead, but you’re going to have to revisit information regardless. You might think, “Oh, but I’ll fall behind.” Well, welcome to PA School! You’re always behind, never catch up, and then you graduate. So in some instances, it’s actually to your benefit to delay when you start studying for an exam to maximize your memory and fight the forgetting curve. And when I say delay, I mean prioritize testable material that’s coming up sooner instead. For my big eight credit class, I would try to study a little bit every day, regardless of when the exam was, but it wasn’t in line with the class schedule. It was just my own personal pace which would then ramp up as the exam got closer. And a lot of that time I spent was just outlining, organizing concepts into tables, and creating Anki flashcards. That’s the stuff you want to have done ahead of time so that when it comes time for that crunch 3-5 days before a massive exam, you have plenty of filtered content already to study from.

What you do in class also matters. For me, what was helpful in class was to be working and doing something active; not just passively listening and jotting down notes. That way I didn’t get home and felt like I had to get started. Read more about that here (Tip #3): https://anthonysorendino.com/blog/2024/8/27/p1-p2-amp-the-top-5-tips-for-surviving-didactic-year

Final verdict: If you have the time to go over content daily, certainly go for it, but plan to revisit the information again at spaced intervals. Your immediate time might be better spent studying for exams you have within the next few days.

You should outline the PowerPoints before class.

I think outlines are valuable. Most of the time, however, I would outline in class because I simply didn’t have time (or energy) to do it beforehand. It’s important to not get slide fatigue. A quantity of 50, 100, 200 slides, etc. doesn’t really tell you much. You need to know what’s inside of them (I would actually use PowerPoint’s word count feature to see how dense the deck was). The third image below shows the deck spread for our women’s health exam. The first number in parentheses is the slide count with the following number being the amount of words within. Included are comparisons to some famous books… for fun.

So make yourself a table of contents. How many “characters/diseases” are here? How many families of diseases/how do they relate? How can you organize all of this? Don’t just make an exact outline; make it work for you and organize it! Information is often presented in a linear fashion, with no real comparison or contrast to surrounding topics.

An outline for me looked like the first image below which I would then turn into a spatially-oriented table (second image) of highlights:

This is why tables/matrices are so valuable as you flesh out your notes. It’s about transforming a linear outline like the above into something more visual. The most important benefit of using a table like this is that your brain will remember where the information was. Oh! I know I wrote Group A Strep on the upper right and that was Guttate Psoriasis. Done.

The reason they say writing with pen and paper is better is misunderstood. It’s not because it slows you down, it’s because you can’t pinch to zoom on a piece of paper. Your brain remembers the scale and weight of information on a physical piece of media. You can zoom into a Google Doc table, but upper right will always be upper right; it’s a digital format that retains the benefit from a printed page. See the section “Enter The Matrix” here: https://anthonysorendino.com/blog/2024/1/1/studying-pa-school-the-tools-of-the-tradein

Final verdict: It’s good to get a glance at what’s upcoming and reorganize the content to your liking. Use tables!

Most students study 4-5 hours after class.

The “time” you spend studying isn’t a good metric at all; it’s how you study and whether it was focused or full of distractions. I think giving students time-based study goals can actually be detrimental because it traps students into thinking longer is better and that they should be staying up later and sacrificing sleep to hit an arbitrary benchmark. Two hours of laser-focused, spaced repetition, spatial-based memory studying beats 4-5 hours of unfocused, passive, interrupted studying every time. I’d also argue that the last thing your brain and body want to do after being in class all day is to study/learn even more. Efficiency of your time is important. How much are you really going to retain when you’re exhausted? I’d recommend waking up early and doing some solid studying before you even get to school. This allows you to take it easier when you get home and actually unwind and recharge your batteries so that you can get a full night’s sleep. I would try to study from 5AM-7AM every morning, seven days a week. When most of your family and friends are still sleeping, you’re not getting texts, you have no new Instagram messages coming in, etc., It’s much easier to lock in during the peaceful early morning hours.

I truly believe that how you study is the biggest oversight in academics because it’s simply not taught. Here’s the process I came up with: https://anthonysorendino.com/blog/2024/6/5/summer-semester-amp-the-problem-with-memorization-in-pa-school

Final verdict: Never measure your progress by time. “I spent 20 hours studying.” Okay, 20 hours studying…. how? Studying what? Quality beats quantity every time.

You have to lose sleep / pull all-nighters.

This one is easier said than done but it’s possible to never sacrifice sleep during your didactic year. Probably my greatest achievement in didactic year was that I was able to get a full night’s sleep for an entire year, including all three weeks of finals. Not a single all-nighter. Not a single late night. Never once did I have more than one cup of coffee per day. Rarely do I flex, but this is my nerdiest weird flex and I’m proud of it. My sacrifice in humility here is worth it to show you that it’s possible. My goal here isn’t to gloat, it’s to inspire. And for the record, I’m no savant. I’ve always been a pretty average student from grade school into undergrad. I was never an honor student, in a gifted class, nor have I ever won an academic achievement award. So if I can do it, so can you.

It’s not rocket science. Going into an exam on little sleep weakens and dilutes all of the hard work you did earlier that day and that week. It’s pretty well documented that quality sleep helps strengthen and build neurons overnight. Sure your all-nighter might have yielded you a passing score, but at what cost?

It’s important to note that sometimes lack of sleep is a deliberate choice and that’s okay. Maybe you had an important family event or a concert the night before an exam. Maybe it was your birthday last night. Striking a work-life balance comes with a price; you just have to decide on a budget. It’s certainly preferable to have a social life in PA school for your general well-being. I’m 35 and live alone with no children. My social life is slightly different than a 22 year old college student or a student supporting a family. Self awareness of the author giving you all of this advice matters; nothing I’m offering here is a one-size-fits-all approach. I’m fortunate for my situation, but I still think with discipline it’s possible to maintain a steady sleep schedule no matter what your situation is. It’s my #1 tip for surviving didactic year: https://anthonysorendino.com/blog/2024/8/27/p1-p2-amp-the-top-5-tips-for-surviving-didactic-year

Final verdict: It’s entirely possible to maintain a consistent and healthy sleep schedule in PA school and I believe sleep should be your #1 priority.

PA School is like drinking from a fire hose with a straw.

Drinking from a fire hose with a straw means that inevitably most of the water is going to go… I don’t know, on the street and into the sewers, instead of into your straw. I always thought of this metaphor as “Okay, I drank as much as I could, I guess that’s good enough.” But the problem is, you need most of the water that spilled out onto the street so you have to get down and dirty and go sewer diving. I don’t know that there is a true metaphor for PA School. It’s sort of like juggling fruit and you have to pick and choose what you want to add into your juggle. A banana? Nah. An orange? Sure, I’ll take that. It’s about sacrifice of content that you don’t think is that important and understanding your limits. You have to let some fruit go and splatter on the pavement. Juggle enough fruit for an exam, finish your routine, and then start a new juggle. And often you need to split your focus and juggle with both hands and sometimes a foot.

Final verdict: This saying simply means “PA school is hard” and really isn’t useful. You already know it’s hard.

PA School is all memorization / regurgitation onto an exam.

This one honestly isn’t far from the truth, but that’s far from a bad thing. I spent most of my later blog posts talking about memory so I won’t repeat everything here. Read more here: https://anthonysorendino.com/blog/2024/6/5/summer-semester-amp-the-problem-with-memorization-in-pa-school I think it’s important to trust the process. The PANCE and Arc-PA have created a giant PA-C creating machine, and you’re a part of that and you have to buckle up and enjoy the ride. You’re not just a student, you’re also a paying customer but in a business model that works.

Over time, the constant smattering of information means that things will begin to stick. You won’t necessarily need mnemonics or charts; you’ll just know it. Minutes after the exam, you start to forget information at an alarming rate. At times, you might not feel like you’re learning much at all. This is all okay. This is normal. Trust the PANCE rates of your program. Trust the numbers. Trust the process! Also, keep in mind that most of your training as a PA is going to depend on your specialty and is going to happen on the job, just like any other job. Your #1 goal is to simply get to that point and pass your exams.

Final verdict: Mostly true, but there’s nothing wrong with that. Capitalizing on memory techniques is one of the most understated “hacks” of PA school.

Don’t triage your studying.

To advise future healthcare providers not to triage was always interesting to me as triaging is the lifeblood of an emergency room, the front door of every hospital. You absolutely should triage and play the numbers. See tip #4: https://anthonysorendino.com/blog/2024/8/27/p1-p2-amp-the-top-5-tips-for-surviving-didactic-year

Be okay not studying as much for the quiz tomorrow in the 1 credit class so that you can study more for the exam in the 4 credit class three days from now. Be okay not being perfect. You’re not going to be able to put a triage “green tag” on every single exam. Sometimes you have to be happy with a yellow and keep moving. Survive any way that you can and constantly re-prioritize based on what’s coming up in the next few days.

Final verdict: Prioritizing and triaging is an important skill in PA school and in life in general. Be okay making sacrifices and playing the numbers.

You should make your own study guides.

As someone who made study guides most of his personality in the first year, this is a spicy one. I think the actual value you get from the process of creating a study guide itself is over-exaggerated. It’s the actual “studying,” the spaced repetition, the free-recall, the deep-dive, the grind, the using of said study-guide where you get the full benefit and start retaining information. I’d make 100+ page study guides with accompanying videos but still needed to “study” it to retain information. The creation process only got me maybe 15% of the way there. It’s not the short-term value of creating a study guide, but actually its long-term use that makes creating your own content a good idea. More on that in a bit.

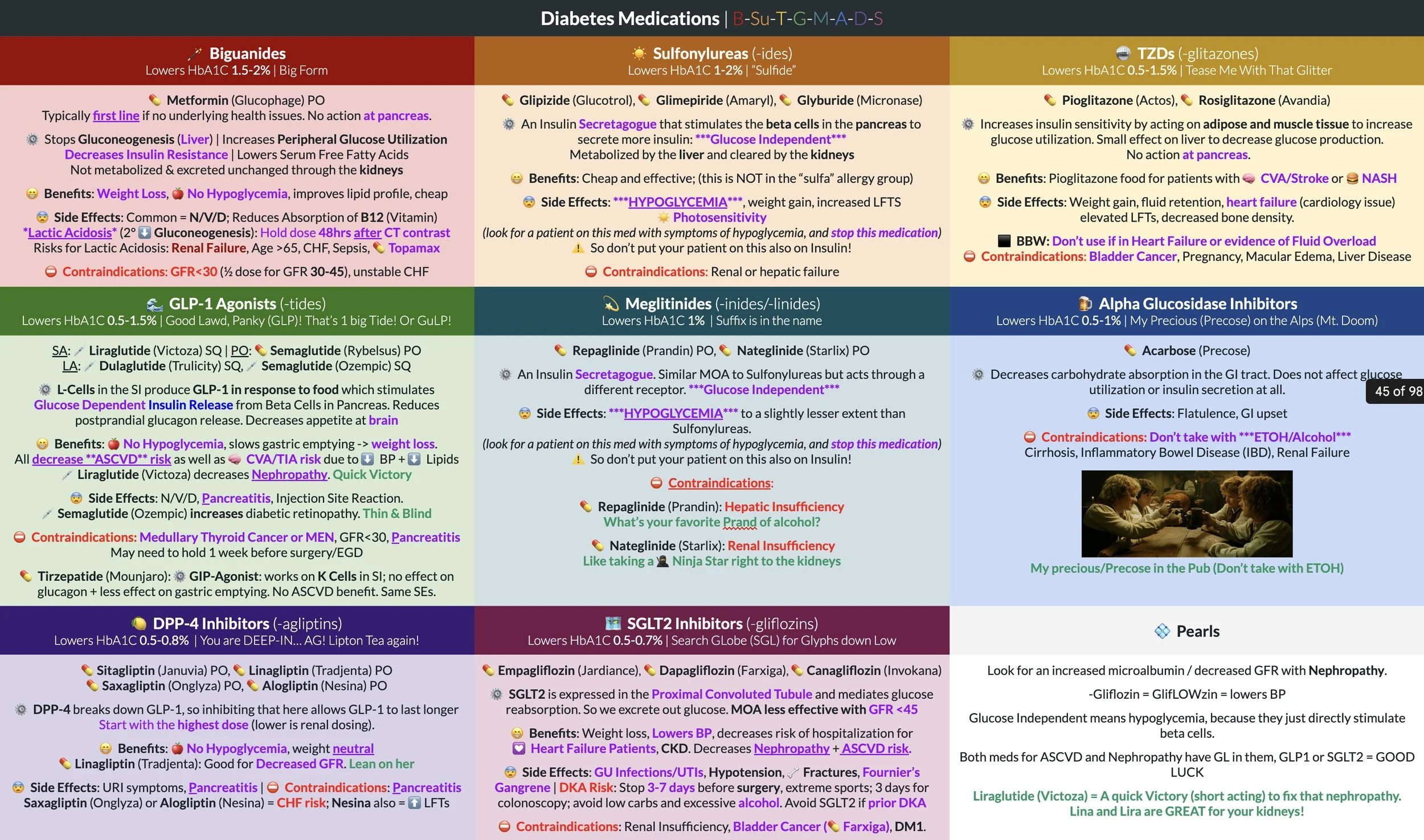

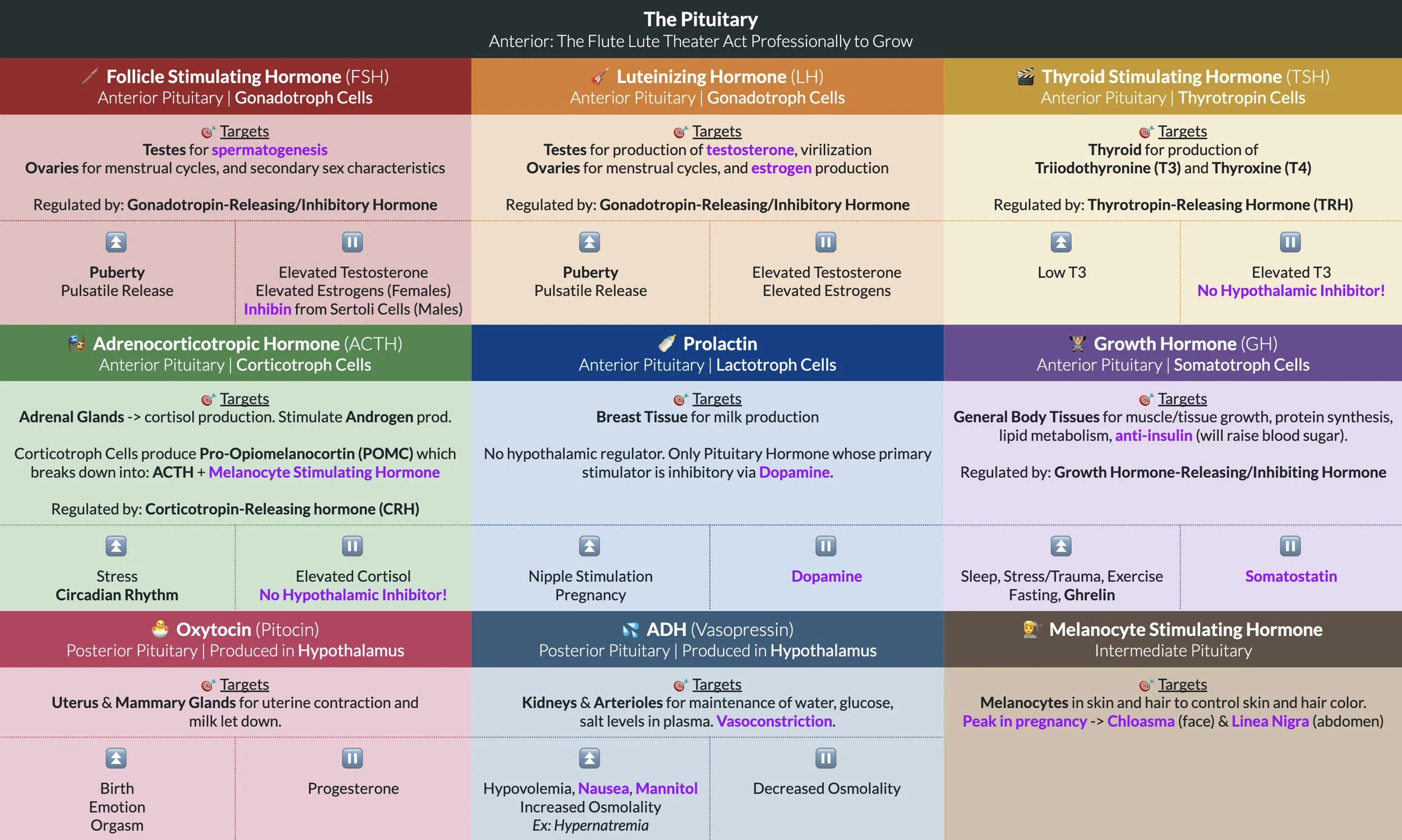

But should you use other students’ resources? I rarely used anyone else’s study materials for a few reasons. I was already putting so much effort into my own study materials, not just from a content perspective, but from a formatting perspective. I probably spent the same amount of time on color-coding, font-size, and finding that perfect emoji as I did with the actual content itself. I’m a stickler when it comes to format; I find that aesthetically pleasing content is much easier and more enjoyable to consume. Color-coding is incredibly slept on as a study tool. I can tell you gram positive from gram negative bugs in an instant because every time it’s mentioned in my notes, I color GPs purple and GNs pink (I also have them in very different memory palaces which make them impossible to forget). Penicillins are orange, macrolides are yellow, fluoroquinolones red. Even now when antibiotics or bugs are mentioned in clinical year, I can feel the color of the medication and instantly know the class. I’ve developed an entire custom color-palette that I carry over into every new Google Doc. Here are some of my proudest examples:

I also tend to have a higher-threshold for what’s important (meaning I would ignore a lot of information). I don’t mean that to sound pretentious. It’s a game to guess what’s going to be asked on the exam, and I feel like I got pretty good at playing. I ignored almost every single lab-based diagnostic workup, not because it’s not clinically relevant, but because it’s not high value for an exam. I cut a lot of corners and just focused on the big picture stuff, plus a few unique things that make a disease process stand out. If your study guides are an exact copy of the source material, just reorganized differently, that’s probably not the best use of your time. I’d really recommend paring it down and using your judgement to just take what’s important. The process of actively filtering out important information is a great way to actively learn.

The value I’ve seen with creating my own study materials is that I constantly referenced them throughout the remainder of my first year and constantly reference them during my second year. It’s very rare that I actually open up a PowerPoint deck and check on the “source” material. To have something meticulously color-coded and filtered, in my own words is so nice to look back on. I also use my notes much more often than Up To Date when initially looking something up during my rotations; I get the big picture from my own notes and can then dive into the recommendations on UTD or a hospital’s preset pathway.

With all of that said, if someone already painstakingly made a flashcard deck for the anatomy practical, by all means thank them for their service and use it. If someone made a nice chart of triads, use it. If someone made a 100-page fully color-coded study guide (ahem) go ahead and use it but try not to become completely reliant on the resources of others.

Final verdict: You can use any study material that you want, however there’s value as a long-term investment to creating your own content to your liking that you can utilize in the future.

This will be the most miserable year of your life.

I’ve heard this more than you might think and I’m sort of mystified by it. Sure there are times where you’re like “Man, this sucks” but I was never miserable. And that’s not even unique to me as an older student; everyone around me seemed to be pretty relaxed and having a great time throughout the entire year. PA school is only miserable if you let it get the best of you; it’s all about your mindset. You were vetted through one of the most competitive application processes in the country. You’re sitting in a seat that thousands in the country didn’t get to sit in. You’re surrounded by people who want you to succeed. You’re learning how to save lives. You’re learning practical, hands-on, skills. What’s remotely miserable about any of that!?

Final verdict: No shot.

You have to make social and personal sacrifices / won’t ever see your friends and family.

This is partly true but not nearly as dramatic as it sounds. I definitely had to make sacrifices like quitting video games, canceling concerts I had tickets to, etc. But I was still able to go to a couple of shows, still saw my family regularly, etc. It comes in waves though. Sometimes you have a crazy week coming up, so you really need that preceding weekend cleared. Then you get a few days to breathe and a weekend where you can squeeze some family time in. Your life certainly will revolve around school, but if you budget out your time, you can carve out time for yourself and others. This is another reason why efficiency in studying, not time spent, is important. Because I was efficient with my studying I was able to take multiple nights off per week.

The video games thing for me is interesting. They’re still one of my favorite pastimes but I knew they would be a time-suck, so I cut them out completely during most of didactic year. I sort of rewired my brain by using video game-like addons for Anki and a Nintendo Switch controller for the Anki cards to make studying as close to gaming as possible. What’s funny is that when you don’t feel like studying, it doesn’t matter what distractions are around you, you’re just going to do something else if you’re really not feeling it. I realized instead of gaming, I’d just be doom-scrolling / brain-rotting on social media, which is much, much worse than a couple hours of Borderlands or Warcraft. So I actually started gaming again late in my last semester. I realized it made me much happier; I felt human again.

Final verdict: Anything worth doing that’s going to create a great career for yourself will come with sacrifice. Carve out time for what matters most. Do what makes you feel like a human.

Your grades matter.

This one might be controversial so buckle up. Do you need to pass your program to graduate? Yes. Does it matter what your GPA is? Not at all (as long as it’s above your program’s requirement). Shoot for 90s and strike a balance between grades and being a human being. Patients don’t care about your GPA or grades if you don’t know how to relate to them on a human level. So don’t be a robot! Some of the most academically brilliant providers I’ve worked with over the past 10 years have a poor bedside manner, and poor relationships with the nursing staff and cost their organization time and money through patient complaints and poor reviews. So in the end, how much did their 4.0 GPA really help them in practice?

I actually think GPAs and awards for high ones are outdated and can be detrimental. Because it forces you to sacrifice to “achieve” a number that’s meaningless in clinical practice. Are we rewarding someone who made unnecessary sacrifices and holed up in their room for an entire year, just to achieve a relatively arbitrary score, one that has no relation to patient safety and satisfaction? It also makes those that didn’t receive an award feel sort of inferior. Does this mean I’m not going to be as good of a provider? (No).

At the end of the day, as long as you pass, you’re all going to be a PA-C. I constantly grapple with that personal reflection of “Am I lazy and doing the bare minimum, or am I striking that school-life balance?” And I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad place to be as long as I am self-aware. I did really well in my didactic year and had a ton of fun while doing it. Am I going to win any GPA awards for being on the bleeding edge of a 4.0? Not a chance, and I’m perfectly happy with that.

Final verdict: Grades matter to no one else but yourself. Your grades and your patient safety and satisfaction scores have little correlation. Patients care about how you make them feel, not your GPA. Find a balance!

Final thoughts.

So that’s all I have for you! If you have any thoughts, please feel free to share!

For this post’s song, I chose one with the word “myth” in the title. “The Myth of Youth” by Geographer is a song I discovered while working in medical education and was actually one I had on a playlist I would play before medical/PA student orientations. It’s so bouncy and catchy and one of those songs where the verses are actually more of a hook than the chorus itself. That first post-chorus around 1:45 is just a symphony of sound that leads into a second verse accompanied by a driving synth and then the second half of the second verse kicks in with that main guitar riff. It’s just a fantastic song.

See you in the next one.