What does throwing a rock and a shoe at Buzz Lightyear’s spaceship, Mike Wazowski chasing a sheep around his apartment while Sully inhales some toxic soup, and a nickel falling from the sky into the volcano of the fish tank from Finding Nemo have to do with infectious disease? Well, if you were me about seven hours ago, absolutely everything.

One of the big problems I encounter with the innumerable topics that we’re responsible for in PA school is that I can’t really speak to any of them in a comprehensive way. I can match the buzzwords like “Owl Eye Inclusions” and “Herald Patch” & “Hutchinson’s Sign” with the correct diseases, but I can’t really tell you about those diseases as a whole. I study for hours but then show up at exam review and completely freeze up at some questions. What I’m doing is working fine for exams, but I feel like I’m missing something.

As we we inch closer and closer to P2 year, the questions are becoming more vignette-focused and they’re giving us less buzzwords and hints. And that’s exactly what we need; clinical year is all about real-life practical scenarios. A parent isn’t going to say, “Hello, yes, I came to get my child’s strawberry tongue, sandpaper rash, and Pastia’s lines checked out.”

I think there’s a really fascinating question in PA school: “Okay, I have X amount of time left to study for this exam. Statistically, what’s the best use of my time?” And sometimes that amount of time is a few days, and other times it’s an hour at lunch. Per minute, what is the most effective, most comprehensive way to learn anything? I’m fairly sure I’ve found the answer.

I picked up a book called Moonwalking With Einstein by Joshua Foer over Spring Break. The book was mentioned in a video featuring USA Memory Champion Alex Mullen, who was a medical student when he learned how to memorize an entire deck of cards… in under 15 seconds. And Alex, along with every other USA Memory athlete all had pretty average memories before they started competing. They’re not savants; they’re just like you and I.

In the book, the author Joshua Foer talks about an experience he had with two other world memory athletes:

“Ed recounted how on a recent visit to Vienna, he and Lukas had partied until dawn the night before Lukas’s biggest exam of the year, and only stumbled home just before sunrise. “Lukas woke up at noon, learned everything for the exam in a memory blitz, and then passed it.”

If what the strategy Lukas used isn’t the most burning question you’ve ever had as a student, then I don’t know what is. Alex, Lukas, and pretty much every other memory champion uses the same strategy as their foundation for memorization. And the answer to “Per minute, what is the most effective, most comprehensive way to learn anything?” I think is unquestionably the memory palace.

An Uphill Battle

I want to say this morning’s exam, on 11 slide decks, split evenly between Infectious Disease (ID) and Neurology was brutal, overwhelming, stressful, and required an unreal amount of preparation, but I find myself saying those words for every subsequent exam so the words are losing meaning. How many antibiotics did we have to know? All of them. How many gram positive and gram negative bugs did we need to know? All of them. I counted 44 individual species of bacteria, all with overlapping symptoms, manifestations, some had single therapy, others had dual therapy, second line, allergies, inpatient, outpatient, prophylactic, supportive, antitoxins, empiric coverage, rashes on the hands, rashes on the feet, blanching, non-blanching, it was never ending. And to me, a task so seemingly insurmountable was extremely enticing.

So is it possible to borrow a trick from a medical student who can memorize a deck of cards in 15 seconds to remember almost every single detail about 44 different bacteria? It is possible, and that’s exactly what I did.

As much as I promote the use of flashcard app, Anki, and previously have had Anki decks with over 1000 cards for a single exam, I just took an exam where for half of all of the content, Infectious Disease, I made zero flashcards. My retention of the information of four entire PPTs relied on scenes from Pixar movies. Here’s an example:

For me, it was all about getting topics down to 7 bullet points. What is it called? How do I treat it? And then what are five facts about it. No disease process fits into a template, so not locking into: “Presentation, causes, diagnosis, labs, treatment” was useful; this process is very flexible. To me it’s “Hey, what are five interesting facts here that I can talk about, and that make this unique?” And sometimes, a disease has 6 or 7 interesting points, so I made some cuts. I can’t, and no one should, memorize every single detail. It’s simply not worth the time. Did I miss some points on the exam because I didn’t bother to memorize all of the diagnostic tests? Yes, but I picked up a bunch of other points elsewhere. Passing exams is a numbers game and you have to play to those. And sometimes that means being comfortable being uncomfortable missing some questions.

How a Memory Palace Works

Traditionally, for a memory palace, you choose a path in your house or any location you’re familiar with and place items mentally to help you remember. For example, if you were trying to remember the presidents of the United States, say when you walk into your house and turn to the right, there’s a table there. Imagine yourself Washing that table. Wash = Washington. Maybe next to that table is a bowl of fruit with an apple in it, Adam’s Apple for John Adams. And maybe next is just some empty counter space and you imagine knitting some Fur for your Son, Jeff, for Jefferson. I promise you, as ridiculous as it sounds, this strategy works insanely well for anything that you want to remember. Show me a list of 25 things you want to remember, and I can teach you how to recall it verbatim, in any order, in under an hour.

The first task I tackled was to cover 21 gram negative bacteria. First, I combed through the slides and picked out five facts from each. I’d remember 7 things in total for each (the name, the treatment, then the 5 facts), giving me 147 bullets of information. And that was just for one of eleven slide decks. Next, I “built” a 21 “room” house, very loosely based on a place I used to live. To be clear, this wasn’t a mansion: I put three bacteria in the garage, two in the basement, put some on staircases, created an imaginary backyard with a greenhouse, etc. What I discovered is that while helpful, memory palaces don’t need to be based on places that exist. It’s like reading Harry Potter for the first time; you had to imagine all of Hogwarts in your head before the movies were made.

Looking at it as a whole, it may look extremely overwhelming. But committing it to memory is actually very systematic, logical, and very fun. Here’s an example of how I remembered Yersinia Enterocolitica:

Once I would complete a “scene” I would look away from the computer and recite the entire thing, even the seemingly extraneous information, like the fact that I was calling an imaginary preceptor. 99% of the time, I could recite it all correctly. I’d move onto to the next scene, recite that one, but then recite the first one again.

After I completed the 21 gram negative bugs, I moved on to gram positives. I decided to place all of the gram positive information into scenes, or vignettes from Pixar movies:

Strep would be Toy Story

Staph was Finding Nemo

Clostridium, Anthrax, Listeria, & Diphtheria was Monsters, Inc.

Lyme Disease & Syphilis was A Bug’s Life

For one of the gram positive bugs, Strep Pneumo, I used Andy’s Room from Toy Story. I pulled images from Google to help orient myself, and just made a story. It’s wild how connections can be made, like using Wheezy for pneumonia, and pulling out his squeaker to do a lung biopsy. Mr. Potato Head was Otitis Media and Sinusitis because he was missing both his nose and his ears. Mrs. Potato head punched him with a boxing glove, reminding me the treatment was Amoxicillin.

The other thing I did, which worked incredibly well, was converting antibiotics to items and people. For example, Ceftriaxone (Rocephin) become Dwayne The Rock Johnson (ROCKephin) or just a rock, Penicillin G become Tigers Woods, or a golf club, or a golf ball, Vancomycin became Vans shoes, or any type of footwear, Flagyl was a flag, Clindamycin was Bill Clinton, or any president, or anything patriotic. Tetracycline was a four-wheeled vehicle, Doxy was a bicycle, and Azithromycin was zit cream, to name a few.

What was so cool about this was that I could combine them either together as one item, like a zit-cream covered rock for Azithromycin and Rocephin, a dual-treatment option for inpatient pneumonia, or as just multiple options, like an American Flag became Clindamycin and Flagyl, or a presidential motorcade became Clindamycin and Tetracycline. That picture above of of Leonardo DiCaprio toasting combines two medications: Cefotaxime is Leo’s character from Wolf of Wall Street who was charged with tax evasion, and anything alcohol related was Ciprofloxacin, like a sip of beer. Placing that image in that scene for Yersinia became an unforgettable way to remember the treatment.

You know what would take a long time to remember? That the treatment for erysipelas, one of the like 12 manifestations for Group A Strep: Strep Pyogenes is either PCN-VK, Clindamycin, or Erythromycin. How do you remember it? Do you make an acronym like VEC? How do you remember what the acronym belongs to? How long does that acronym take to learn? How many times do you have to brute force repeat that flashcard? How do you know the C in VEC doesn’t stand for Ciprofloxacin or any of the 27 Cephalosporins?

A few months ago, I would have chosen one medication to remember, likely the first one mentioned on the slide, but with the memory palace, it became almost effortless to remember multiple medications. For me, I was in Sid’s room from Toy Story, slipped (erySLIPelas) on a red-rug (that later raised like a plateau, the description for erysipelas), and a volley-ball net pulled us up like a trap (Volleyball = PCN-VK), Abraham Lincoln, who I had just freed from a Cell (Lincoln = Clindamycin because he’s a president, but also this is a Lincosamide, and this also treats Cellulitis), was trying to break us out of the net using his top-hat, but we were all jammed in this net because Clifford the Big Red Dog was also trapped in this net (Clifford = Erythromycin). That’s not something you forget easily.

What I loved about this strategy, besides it being a ton of fun, was that I could recall an entire disease process from front to back from memory after about 5 minutes of work. The key, however, was to repeat it again a few minutes later, about an hour later, and then the following morning, and then once three days later (this battles the forgetting curve). I’d miss details here and there, but I’d recall over 90% of the “stored” information each time and pretty much never had to look at it again after that third day. And even if I didn’t remember everything, I’d remember where I last left it.

Confidence

Another thing I liked about this strategy was the confidence it provided. Many times I’m asked something and I’m like “I think it’s this.” With a memory palace, there is no “think.” Which gram negative bug is more dangerous to patients with Sickle Cell? Well, there’s a giant Grim Reaper with a Sickle in the basement I used to live in, next to little Timmy who’s on the last legs of life, standing in front of a Salmon-filled fish tank. There’s no doubt in my mind that it’s Salmonella. How do you treat a kid with that? Fulfill his Make-A-Wish and have him meet The Rock (Rocephin). That one’s a little “grim,” but the more ridiculous you can make the story, the better. If a mnemonic can make you laugh, if you can work humor into your studying, you’ll start remembering more.

Before going all-in on the memory palace for this portion of ID, I tested it out for parasites and fungal infections for the last exam. A really fascinating occurrence happened just minutes before the exam started. I was talking with another student and a pretty interesting question came up that we thought might be asked. However, between the two of us we couldn’t remember which of two disease processes this question belonged to. The more I thought about it, however, I was 99% sure which disease it was. Why?

Because the last place I had left this piece of information was in a thrift store I used to work in, surrounded by Lenox porcelain figures and high-end hand me down clothing. The other disease in question was in an imaginary restaurant nearby with flat worms and trematodes.

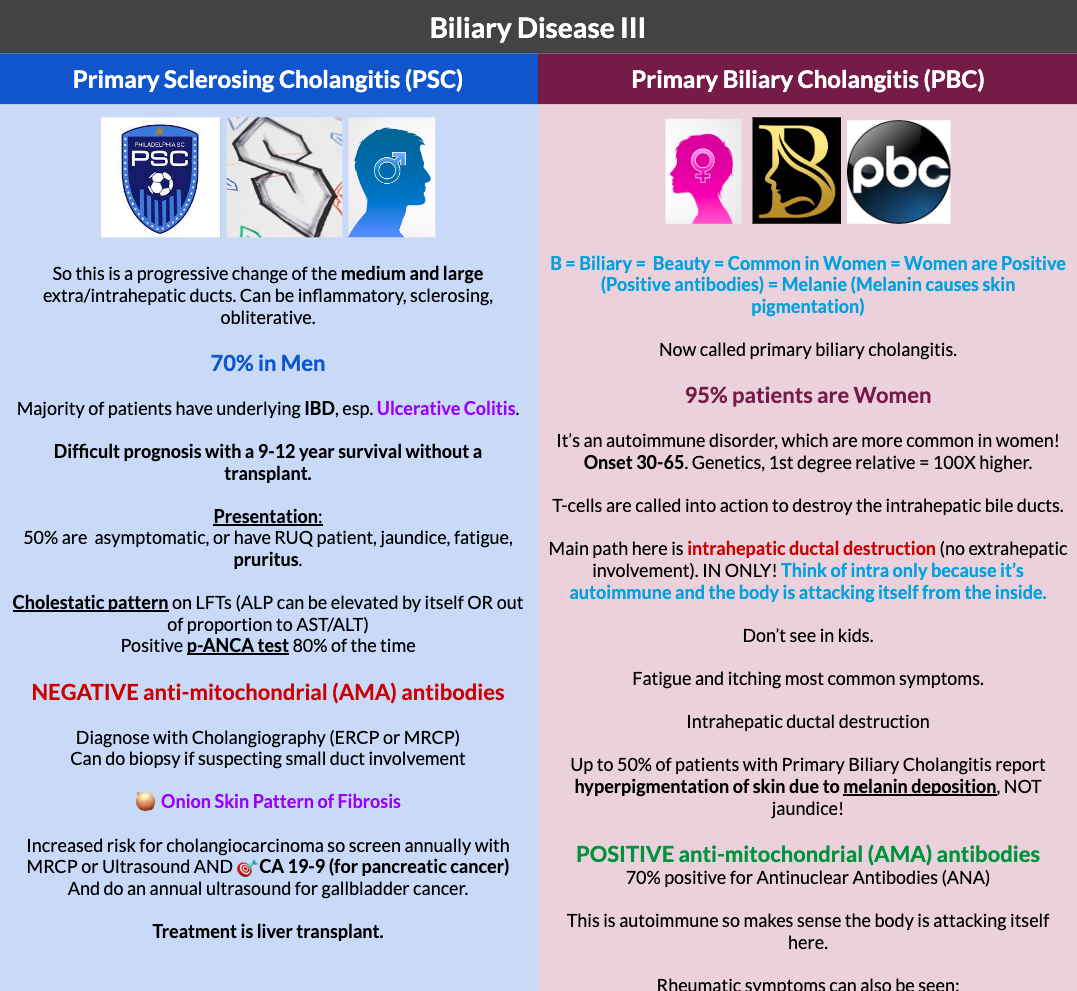

A plague to the memory of a PA student is interference: getting two disease processes confused. I’ll hit an exam question and I’ll remember this buzzword was on the upper left of a chart I made… but both Measles and CMV were on an upper left corner of two different tables and I couldn’t remember which it belonged to. A memory palace is the greatest insurance to this because not only are these topics no longer in similar tables, they’re not even in the same movie or zip code.

Free Real Estate

So back to the original prompt: I talked about Buzz Lightyear and meningitis already.

What about Mike Wazowski chasing a sheep around his apartment while Sully inhaled some toxic soup? Well, that represents Bacillus Anthracis, or Anthrax. I didn’t need a mnemonic to remember their apartment was Anthrax; they just become one in the same. After Mike caught the sheep (a vector for Anthrax), he got a black eschar. Meanwhile Sully was cooking soup and inhaling it, but he was inhaling Anthrax, and he got mediastinitis.

And what about a nickel falling from the sky into the volcano of the fish tank from Finding Nemo? For this exam, the most overwhelming bug was Staph Aureus, but I worked every important detail into made-up scenes from Finding Nemo. So for Staphylococcus Scalded Skin Syndrome, I pictured swimming into the fish-tank volcano in the dentist’s office from Finding Nemo, where there were a bunch of babies with exfoliating skin, like a spa. And underwater, you look up and a nickel falls out of the sky: Nikolsky Sign.

This process is fun, but it’s not easy. It’s definitely time consuming but to me, it’s time well spent. It’s the only study strategy I’ve ever used that provides a comprehensive, logical, and incredibly organized way to recall information. You already have the layout of your room, your parent’s house, your gym, or your favorite movies permanently in your long-term memory. Those neurons are free-real estate. Use them!

You can’t use a memory palace for everything. It works best with long lists and topics with multiple “buckets” and ID was perfect for that. When you need to tackle multiple different topics in a pinch, it works wonders.

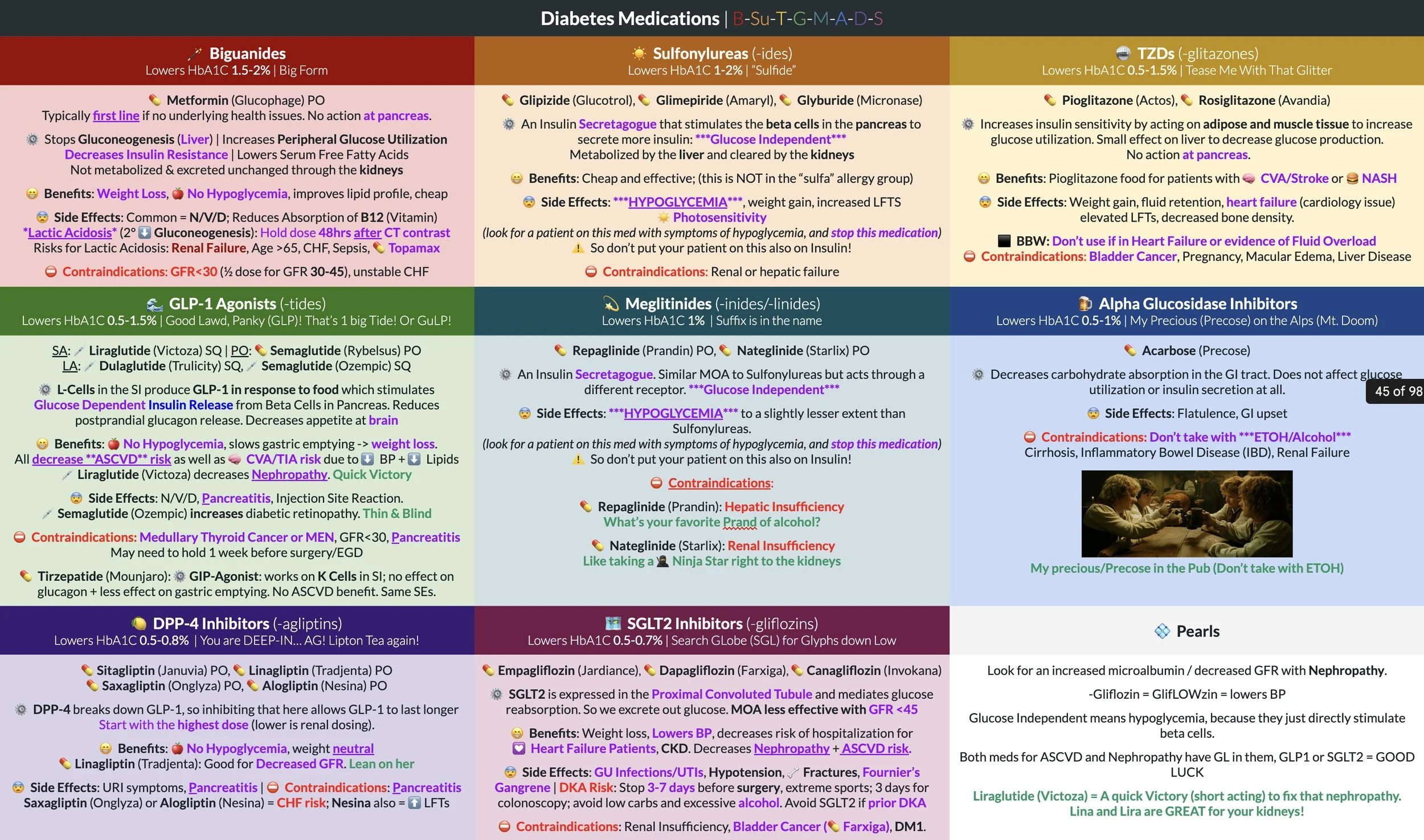

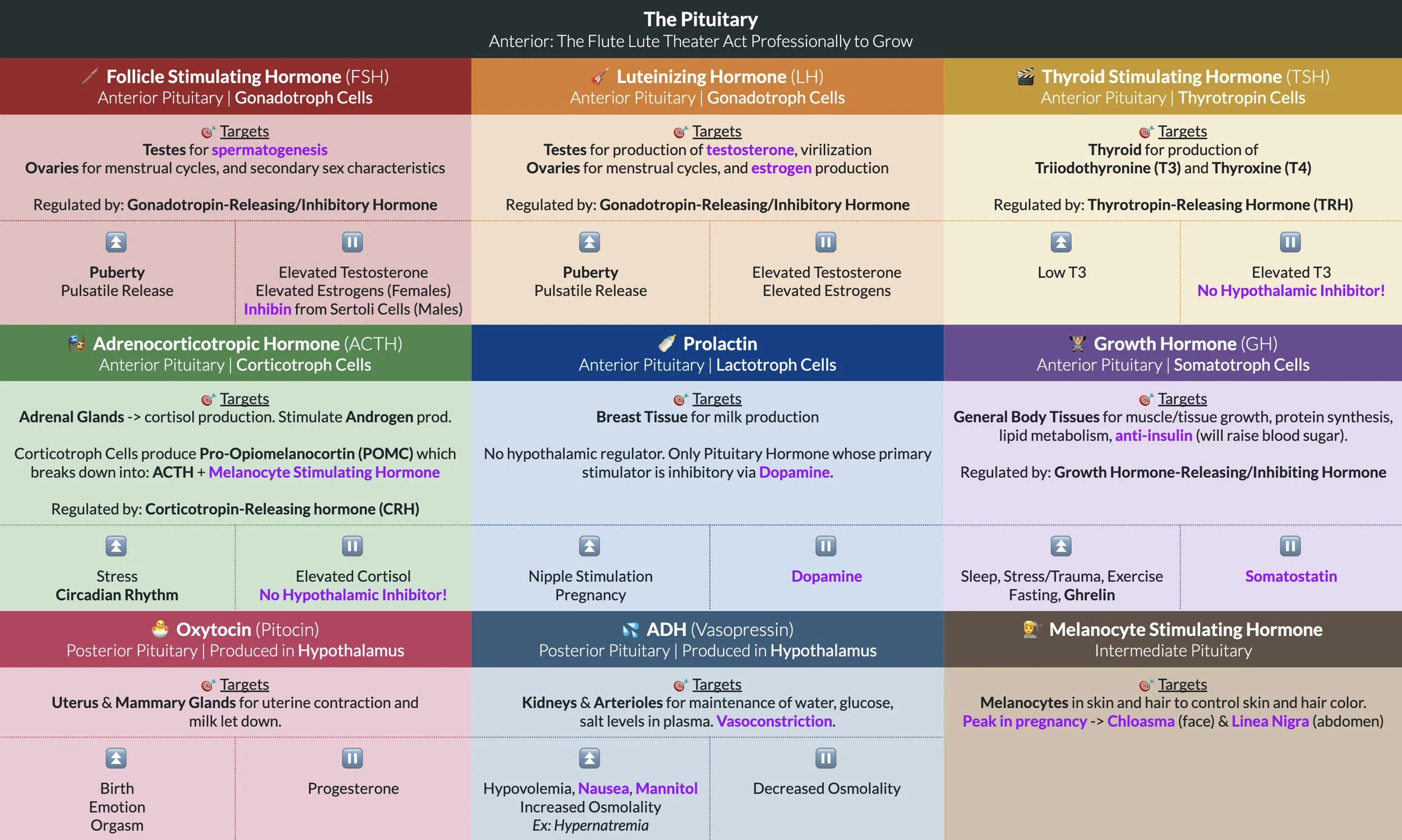

PA School isn’t all memorization, but it’s still a lot of memorization. And knocking out the laundry list of contraindications for TPA, triggers for a migraine, causes for elevated amylase, and every other list that exists so that you can focus more on the pathophysiology and the why is pure gold. When a large percentage of your time studying relies on memory, why not borrow techniques from people who practice it as a hobby?

P.S. I recorded myself making a portion of this memory palace which I’ve uploaded to my YouTube channel. You can view it here.